Is Angela Merkel the master coalition builder? Or perhaps the conservative German Chancellor is just the luckiest politician in Europe at the moment.

On Catherine Deneuve and #MeToo

Smiling, her eyes alive, French actress Catherine Deneuve stepped down graciously from a dark car on the Champs-Elysées. Already of a certain age, as the French elegantly describe it, her heart seemed to leap with the riotous white of a bouquet of roses offered by a suitor in the crowd. This was the official film of the 2012 Paris Olympic Games bid, and when Paris eventually lost to London, the film was blamed for being Old Hat.

Yet for an Anglo-Saxon, it mirrored both the romance of Arthurian poetry (la femme on a pedestal), and the Romantic period itself (love more heart than head), with a touch of 16th century French poétesse, Louise Labé, thrown in: “Kiss me; kiss; kiss me again” — the first line and title of her most famous sonnet.

Catherine Deneuve, the mysterious — the transgressive — whose controversial letter signed with 99 French women this week, criticised the #MeToo movement for “puritanism”. Well, she long ago entered my catalogue of extraordinary Gallic women, joining Simone de Beauvoir of the “The Second Sex” — the title politically incorrect today — Françoise Giroud, co-founder of newsweekly L’Express, and Elisabeth Badinter, alongside Julia Kristeva, Simone Veil and more recently, Juliette Binoche.

Badinter’s book “XY: On Masculine Identity”, explored the possibility of non Rambo-type role models for men, which seemed to me far more relevant than the so-called Men’s Movement around US poet Robert Bly, urging that males paint themselves and run through the scrub, or sit nude and screaming on the couch, to reconnect with their animal side.

De Beauvoir’s opus felt like a line from John Irving, “If life is a forest, women are the trees”, because it put the words of a highly articulate humanist woman, on subjects like women and “The Mother”; women “In Love”; women and “Sexual Initiation”; “The Married Woman” and “Prostitutes and hetaeras”, in a way that educated men, too. And Françoise Giroud? Well, she trounced the achetypal tousled French intellectual, Bernard-Henri Lévy, in a best-selling series of dialogues called simply, “Men and Women”. In an interview to promote the book with the Paris correspondent of The Times of London, clearly in thrall to her, she cautioned against harbouring illusions. “Women can be as cold as ice,” she told him, “with barbed wire in their hearts”.

The French adjective for this all would be romanesque — novel-like or novelistic — but the common thread is the way women and men interact, a very French subject and pastime.

Anyone who has lived in Paris can vouch for la différence; or at least, this difference, in everyday life. It’s evident in the sense of public display and preening in the streets, a long, meandering promenade through which, must rank as one of the peak experiences of modern urban life, to borrow from Australian art critic Robert Hughes.

As well, the French are just generally more relaxed about the human body than Anglo-Americans — about its discrete veiling, or unveiling, depending on how you look at it. This is why the windows of chemist shops in Paris can, well, set the ordinary male pulse to racing.

How to keep a lid on the rage one feels at the physical abuse of women? Which after all was the first preoccupation of the #MeToo movement. As the father of a girl still blissfully free of adult problems but showing the first signs of adolescence, one thinks of Ingmar Bergman’s film The Virgin Spring where the father, in a blind fury, shatters the bones of his daughter’s assailants like chickens against cave rocks. Better to say: those who commit rape or sexual assault should face judicial proceedings, as the former USA Gymnastics team doctor Larry Nassar did this week and Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein surely must.

But it remains true that women in France are à priori less suspicious of men, French men more broadly interested in women. In the Anglo cultures, and especially in the litigious US, mutual resentment has reached such levels that a solitary man, we’re told, can be scared to share a lift with a woman and vice-versa — her because of sexual harassment, him because of a possible sexual harassment case. This is an awful situation for any society to be in, non?

Ms Deneuve ultimately symbolises the view that something of our better selves continues to reside in contact with the opposite sex. For seeing her letter in these terms, I’m sure I would have her respect. I hope that I would also have that of her opponents.

A dangerous combination: Revisiting the Paradise Papers …

Exhaustive media coverage of Donald Trump’s large, highly selective tax cut has highlighted a regrettable aspect of the Paradise Papers, which detailed how some of the planet’s richest individuals and companies avoided payment of billions of dollars in tax by using offshore tax havens.

Crocodile Dundee in Munich: the sequel that never was

With Munich’s famous Oktoberfest coming to a climax this week, clam-handed castaway RICHARD OGIER has the city’s DIY denizens decidedly non-plussed.

A friend whose hair, I think it’s fair to say, is receding faster than mine, has sent me a link for an Australian TV commercial that promises the wonders of “German engineering, for your hair”. A car could be a shoebox on wheels but with German engineering will purr like a pussy cat — years of exposure to television advertising has taught us that. But German hair?

Something called “caffeine shampoo” that comes from an aerodynamic red-cap bottle purports to carry the secret of an eternal head covering for men. The original version, going by You Tube, is English, and shows a suddenly caffeine-energised red hair pushing along a white background, like a sunburnt worm spiralling through a snowstorm. Well, if the Brits are dopey enough to vote for Brexit (delisting 60% of exports and blaming foreigners for it), they’re silly enough to still be making ads with guys in white lab coats talking animatedly about a computer graphic. But I am susceptible. At 52, though my birthday was only recently, I have deplumed at the crown to the point of sporting what most of Sydney now calls, I’m told, a “mosquito launching pad”, which in my case qualifies as cute humour because you could stand a tray of drinks on it.

When I moved to Munich from Paris three years ago, the most important thing for me was to attend the Oktoberfest, 10 days of drinking cold beer with six million others direct from glasses big like milk tankards. Second was to get myself a top-line BMW.

Like degustation of the finest wine when in France, high in the expat male mind upon moving to Munich is that ‘Beemers’ are made here. “A beautiful car, but is it really better than its rivals, though certainly more expensive?” cautioned a French friend who has recently converted — from Peugeot to Renault. He said, “it’s merely a symbol of success” which naturally is why I want to see myself driving the streets of the Bavarian capital in one of these babies, the slightly receding but otherwise elegantly ageing virile type. Cruelly, my wife punctured my Luftballon by heartlessly pointing out that we can’t actually afford a “what, Series 5?” (self-parking 7, she meant), what with the Paris mortgage; rent in Munich; school fees; my Irish “sinking fund” and — oh alright! — the additional financial drain of my laboratory hair replacement program.

But Germany’s flair for engineering and building stuff has manifested itself in ways I didn’t expect. I shuddered at the news that a lift was to be installed in our building and that there might be, as Gert the elderly neighbour explained it, “some disruption”. Well, the works-in-progress were tidier than the kids’ room. The lift-builders, all dressed the same, put multi-sided metal bits in neat piles behind a little rope at end of the day. I came home one afternoon to find Gert (still with all his hair) standing po-faced among the workers. “We have struck water”, he told me. Over his shoulder, at the bottom of a seemingly interminable mine-shaft, I could see a guy thigh-deep in swishing water, a flash light on his helmet. I imagined hearing the slow yawing of bending metal for weeks afterwards, like the crashed plane parts floating in the sea when Tom Hanks goes down in Castaway but miraculously survives four years alone on an island chomping into raw fish and drinking coconut milk. But really, almost nichts (nothing — I’m taking lessons). The water problem was fixed; the lift just went in, all glass and light metal. I can tell you, the experience really marked me.

I can’t claim to be exactly handy but it never mattered before I moved to Munich after a long stint in Paris. Some of my best friends are jazz musicians, notoriously unhandy as a rule — one, I recall, as good as ruined a door trying to change a lock. My German landlord, a big Bavarian with a bouffant who speaks American english like a native (though loudly), put up a bedroom blind when we first moved in — this is true, Mr Trump — in about nine seconds, to the astonishment of my wife. (When I read her draft excerpts of this text she said, “that’s rubbish. It was 90 seconds”). Admirably on a later visit, he tried to hide his irritation, in psychology I think it’s called “rechannelling”, when after a long lesson I still could not “do the hoses” to re-fire the hot water system when rising pressure cuts it out. This he did by telling me he had greatly amused a group of dinner guests explaining that he had a new Australian tenant who was not handy. They had all seen the Crocodile Dundee movies, so assumed I could — I’m paraphrasing — open a can of white beans with a long knife. I could see in my mind’s eye his big frame bent double over the table, dinner guests laughing like hyenas at tales of the new Oz tenant useful around the house like a farting old dog.

Engineering, building and fixing stuff I’ve come to think, is linked to good civic behaviour — what the French refer to as civicisme, without always indulging it. In Munich they recycle à tout va, at the local swimming pool via a quite complex system of colour-coded bins (like the markedly less efficient red, green and yellow boxes of world trade negotiations). And how’s this for a statement of state-directed purpose? The Isar, the river that flows through the centre of the city — like the Yarra, Thames or Seine — was depolluted and cleaned up about ten years ago so that vast numbers of locals now swim along its white-stoned banks in Summer, hardly a broken beer bottle in sight. And this from a region with some 40 beers types, 627 breweries and more than 4000 beer brands. Perhaps it’s in these little ways, and not the grand gestures, that a city shows its true colours? A city that had the heart and soul but crucially also the organisational talent, to welcome 20,000 refugees in a weekend at the top of the European migrant crisis in September 2015.

At the news-agency across the street, I can leave a set of keys. The ground-floor hairdresser takes parcel deliveries for everybody in the building. Less appealing is that one is expected to do the same. Meaning that if you answer your inter-phone to the postman, Amazon or any other brand of brochure, brush or broom pedlar, he’s on the way up. No matter that his delivery, for which you must sign, is for neighbours unknown to you — or for young David across the hall, and his Iranian wife Sarah, who knocks at the door with saffron soup on special days, the significance of which she explains, but who otherwise we never see.

Other little boxes can be found at the mouth of the Metro. These are newspaper dispensers. You lift the plastic lid, put in the coins, and take a copy, feeling like a pleasantly upright Münicher. Once I was short 20 cents and felt wracked with guilt at helping myself, anyway. I returned to pay up later. It flashed through my mind relaying the fact of these things to my French mate, to stop by late at night in his new Renault and pick up a couple, for my font door or to position neatly in a corner of the living room, so that party guests might help themselves to a free paper when they visit.

Flushed by modern Munich’s sense of the collective, the good samaritan spirit, I took to turning in my chair when first here to talk to the locals in beer halls and cafes in basic German — oh hell, English. My entreaties would fall on deaf ears. There’s little or no eye contact in Munich, especially with the opposite sex. You can walk along a viaduct in Paris, see a beautiful woman in the street 20 metres below and she will, as if wearing ball-shoes, spin around in a second to spot you looking. I always feel embarrassed: the eternal guilt of the 1980s-reconstructed, feminist Anglo-Saxon male. Looking dishevelled. No German engineering in the hair.

Mark Twain wrote a famous essay about the confusion inherent in “the girl” being the neutral “das” Mädchen in German, but that’s nothing. Much harder is the second verb at the end of the sentence (“I wish I could do it”, becomes, “I wish that I it do could” — and which “could”?) Well, try that fast after a few litres of beer at the Oktoberfest. But Twain was right about the fiendishly hard road to mastering the four cases, which change word-endings. So “a problem” with the hot water system would be “das Problem”, but more than one would be “die Probleme”, while with (all) these problems “mit diesen Problemen”, you’d rather just be back at the office, or trying to put a bedroom blind up against the clock.

The Brexit Brain-Buster: the ramifications of Brexit go well beyond the EU

With the consequences becoming clearer, the Brexit brain-buster must be sewing the seeds of doubt among some monarchist Australians, including those former Prime Ministers who variously backed and congratulated the Brits for choosing to go it alone in last year’s Brexit referendum.

What the German election tells us about the multiple non-truths of populism

Perhaps the biggest international lesson to be drawn from the German election results is that many liberals, reformists and conservatives — so people from across the political spectrum — should be modifying their discourse on Germany, its chancellor and above all, populism.

Merkel shows the rest of the world how to be a true leader

With Germany facing elections on September 24, here’s a clue to the nation as it is, how it’s travelling, adapting – its fit in the world, when the most powerful and oldest democracies, the United States and Britain, have taken a resolutely populist turn. With a 13– to 17-percentage-point lead in opinion polling, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who opened national borders to a staggering one-million refugees, looks set to be re-elected for a fourth consecutive term.

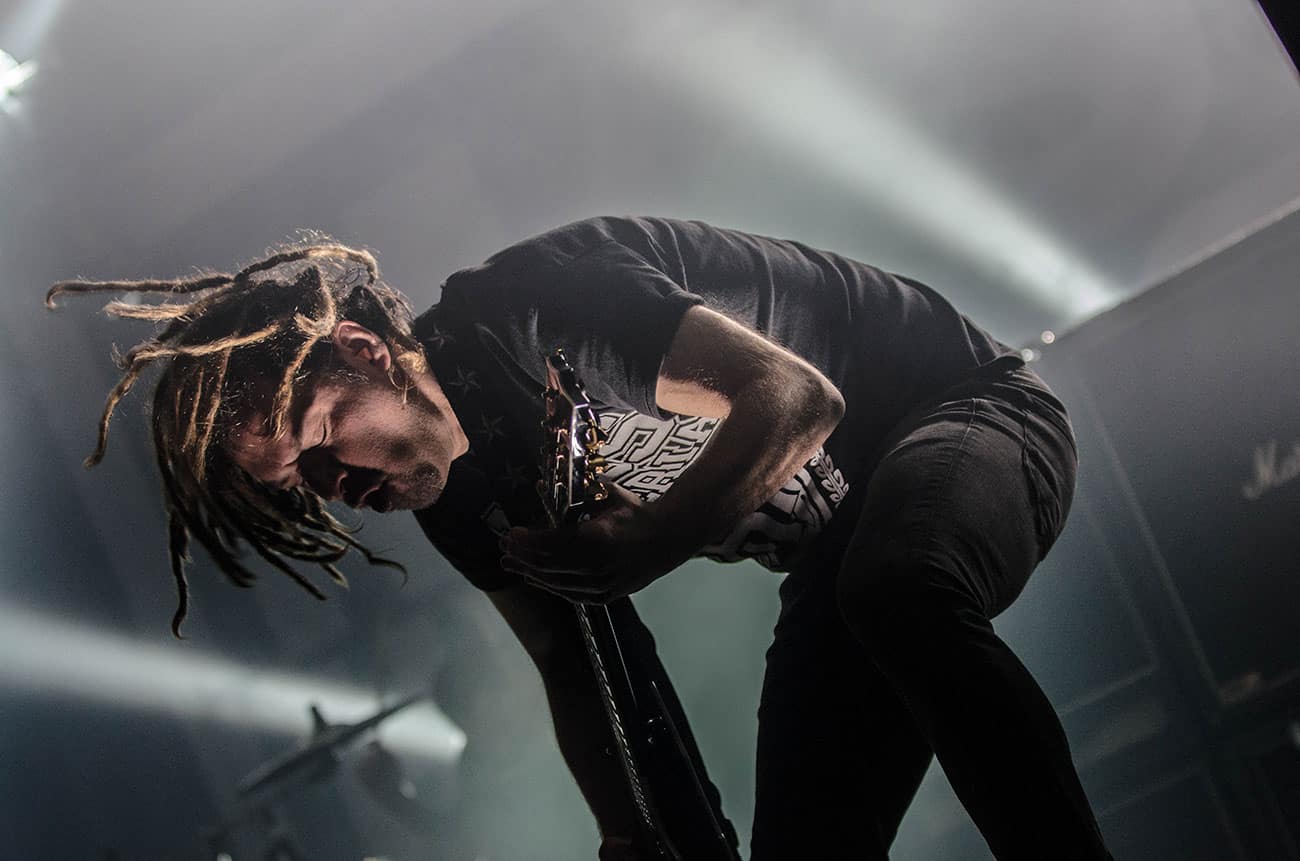

On Munich heavy rock and metal

Heavy metal? In conservative Munich? Yes, a relatively small but veritable, varicoloured scene. And it’s no surprise, says Randy M. Salo, a Munich-based documentary-maker pointing at a thick book on a desk in front of him. Looks like a government report, I remark. Well, it’s conference papers about heavy metal, he says, drawn from a recent gathering in Helsinki that explored the link between the rich world and the “counter-proposition of metal”.

Born into a Baptist family in South Carolina, Randy moved to wealthy Munich in 2011, not long out of film school in New York and something of a progressive metal bass-player himself. I know my Jaco Pastorius, I think of telling him. But instead say I’m a Miles-Trane freak — Miles Davis 1969-75 (adjudging it judicious to quantify) — then to Hendrix; James Brown; Sly Stone; Karlheinz Stockhausen and his trumpet-playing son Markus, by the way, whose god-gifted sound gives me goose bumps … And John Coltrane? Well, there was something ‘thrash’ in the animism of his music after 1965 — like waves breaking on a glorious shore. Here we reach the limits of our shared musical ground, but it’s been a nice contact. He promises to email a list of Munich bands.

The spirituality in the material he signals (check out the cover art of Heretoir’s “The Circle”), has clearly sprung from fields of sound to which Coltrane’s animism, let alone Markus Stockhausen’s clean-line trumpet, would never take me (nor for that matter would his sometime record company, Munich-based ECM). But there is, man, a mothering white guitar player, as Miles might have said, in Randy’s film of a skate punk group called Straightline, that stands my ear on end. A priori, it’s not my thing, but so what? The guitarist-singer, called just Bart, plays lines that motor — forceful, intense, mordantly inventive. He tells Randy’s camera he started out playing jazz.

I take this Straightline to the stoner rock cum groove metal of Godsground; Smoke the Sky (its fans known as “sky-suckers”) and fuzz box three-piece Swan Valley Heights; to the catchy experimentalism of Majmoon (pronounced: My-moon); Mr Serious and the Groove Monkeys — by now we’re a long way from metal — and the ambient post-rock of Pictures From Nadira, whose appealing self-titled debut album, released end-2016, plays as a continuous set. Miles’ “Panagea” flashes to mind — it must be that alliterating “a” — because these pictures have more in common with Tortoise’s “Millions Now Living Will Never Die” (especially the second track, Glass Museum). This I first heard in Adelaide, Australia’s protestant, God-fearing city. It was 1996 and I’d bought “Millions now living”, with its low-cost cover of stencilled fish (to feed the millions?), because listed among the year’s best by clued-up British music magazine, The Wire.

At Munich’s hardtack end, Hailstone sound to me like Real McCoy traditional metal, though proudly bill themselves as “melodic death metal”. To the uninitiated, the word ‘melodic’ — taken from the way certain Gothenburg Swedes inflected “death metal” in the ’90s — stretches the term, given the unrelenting bass drum “blast beats” and growling, Cookie Monster vocals. Heretoir, of the startling cover-art — what is it about Germanic culture and the forest? — typically combine translucent guitar and layered harmonies, with a devouring, ear-shredding vocal. But I’ll admit to a weakness for the last album’s most consonant track, “Golden Dust”, where vocalist David Conrad switches to vocals chant-like and clean.

The Munich metal scene undergoes the usual ups-and-downs, like any minority music, but is active, collegial and pretty well-organised, with numerous venues, two decent-sized festivals and a dizzying array of sub-genres. Randy tells me a “retro” brand of stoner metal, “doom, very analogue”, is currently popular. We’ve met again, this time for lunch in the retro “Baader Café”, a vast rectilinear stockpile of cassette tapes behind the counter to the right as you enter. As in other places where Metal is strong, like much of Scandinavia, the genre’s vehement ferocity equals rebellion against the nice life normalcy of a city with full employment and good wages, so plenty of spending money for gigs, recordings and all that archly boy’s club “merch” beloved of metal heads: caps, “zippers” (actually just tops with zippers), exploding head t-shirts and the like.

I look for Straightline’s album “Vanishing Values” around the corner from my apartment in a tiny record shop called Public Possession, access from the adjacent skateboard retailer is literally through a hole in the wall. Here an outsized black and white sign plonked in the middle of the floor reads: “Reasons for joining? None.” An earlier sign had read: “We went out of business years ago”. Occasionally, I’ve seen groups of people hanging out drinking in the street in the evenings or on Saturday afternoon, apparently connected to both the skateboards and the vinyl.

I moved to Munich almost three years ago, after 17 in Paris, and have come to see the Bavarian capital as a series of counter-propositions: seven state-subsidised orchestras and a metal scene; FC Bayern, the silver-tail football team, and Munich 1860, purportedly the working man’s club. Rich, yes, but largely without ostentation, Munich took 20,000 asylum-seekers in a single weekend at the top of the EU refugee crisis in September 2015, that’s the number then-British PM David Cameron pledged to take over five years. Sleek, Munich-made BMWs glide noiselessly down city streets that smell of cow shit — or can do, as my Franco-German wife had warned me. I was open-mouthed at hearing this, until one breezy, blue sky morning, the rarified effluvium actually touched my nostrils, and the back of my throat (well, my mouth was open). For the record, it was at the corner of Baaderstraße and Buttermelcherstraße in the trendy Glockenbach quarter. Pre-high tech, pre-big finance, Munich travelled the rural road to Bavaria’s first-stage post-war wealth, atop the cow, and particularly, the pig.

“Vanishing Values”, when I finally get it home, leaps from the speakers and takes a hold of my throat. Full-on, the best of it — a track called “Holy Wars” — features Bart’s guitar furiously soloing on an arpeggio played very fast. But it’s there and it’s gone. I reckon Miles would have had him play longer.

“The Munich metal scene is bigger than I thought it would be when I first arrived,” Randy tells me. His production company plans to keep the Munich Unsigned tag, but is branching out into non-Munich bands under the FreqsTV moniker. Both are on You Tube. Randy wants to grow the firm, he says, take it global, while staying, like so many of us now in the Bavarian capital, resolutely international local.

Getting rocked & metalled in Munich

Album: Nadira

Track: Rijl Al Awa

Album: The Circle

Track: Golden Dust

Album: Swan Valley Heights

Track: Alaska

French national elections mean Macron’s ‘revolution’ is now complete

The shorthand on June parliamentary elections in Europe looks like this: newly-elected French president, Emmanuel Macron, 350 seats; British prime minister, Theresa May, minus 12 seats.

Pictures: https://www.istockphoto.com/de/fotos/french-elections?mediatype=photography&phrase=french%20elections&sort=best

Will Macron’s fledgeling political movement break out and fly, or die in the egg?

Just as the fog was beginning to clear for France, with the election of positive-thinking reformist President Emmanuel Macron, old demons of the French political culture have again reared their ugly heads. And the consequences could be dramatic.

Two ministers have become enmeshed in ethics scandals that risk compromising weekend legislative elections for the government, rendering Macron’s revolution stillborn via the ballot box. Whatever his successes out-tweeting — out-smarting — Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin on the international stage, his first weeks have been sullied at home, and he will be blamed. But to what extent?

Should Macron decide to dismiss Richard Ferrand, his regional development minister and former campaign manager, and junior minister Marielle de Sarnez — both facing separate media allegations of sleaze — he would be charged with summoning a spectacular storm upon the government. If he doesn’t, and it appears at this stage that he will not, he could pay the price for ignoring one of the biggest lessons of the current electoral cycle: the French are tired of scandals and want exemplary behaviour from politicians.

The dilemma of France’s youth: vote fascist, vote technocrat or don’t vote at all?

As in cinema, France is home to auteur politics, where the central figure of the president is responsible for story, script and direction. Consider that he’s also perceived as the star of his own movie, and one begins to see the power and responsibility of the president as “republican monarch” in the French political system.

The French presidency is about great politics, in the Platonic sense of would-be great men facing a series of make-or-break tests in a febrile kingly court atmosphere (France has never had a female president). Seen in the these terms, Macron is the latest in a long line of great and flawed presidents, from the Olympian war leader and statesman Charles de Gaulle to the Florentine intellectual Francois Mitterrand, but also including the pre-revolutionary kings of France (on election night, Macron emerged walking sombre and solitary among the classical statues of the Louvre).

With parliamentary elections in two rounds on June 11 and 18, Macron’s next major test, as it were, is in casting. The centrist broke the back of the French party system of left and right in May presidential elections; named as promised a cabinet drawn substantially from civil society with members from both sides of politics; and reinvigorated the French trope of the “Jupiterian” president — referring to Jupiter king of the gods in Ancient Rome, though equally, if unintentionally perhaps, the distant orbiting planet that, floating above the melee, doesn’t actually touch the Earth of everyday problems. In France, the fuss and muss of ordinary, as against great politics, is the job of the hapless prime minister, also appointed by the president.

France has been in a rare, glass-half-full kind of mood lately. Macron’s win felt like relief then a rampart against rising populism in the West, with Trump pushing the US to the verge of institutional crisis and a Brexiting Britain stuck in electoral mode (Manchester and London traumatised by terrorism; the city under pressure; the currency down 15%, hurting wages and savings).

Rundle: on the troubled streets of a France that’s burning

Confidence in Macron as President is up some 10 percentage points since the poll, raising the possibility that his fledgling Republique En Marche (REM) could now win an outright parliamentary majority — meaning 289 of the 577 House of Assembly seats (one poll according REM even 320-350 seats). Alternatively, he could win enough seats to govern with the left of the right and the right of the left. Herein’s the rub, in fact, because a hostile Parliament would curtail Macron’s capacity to counter nationalism, structure European reform with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and implement the kind of liberalising economic reform France so desperately needs.

Enter the ethics controversies, with Ferrand facing “preliminary judicial investigation” for allegedly helping his romantic partner in a 2011 real estate deal with a mutual insurer he managed. He also stands accused of employing his son as a parliamentary assistant and failing to declare it. Sarnez’s name appears on a list of 19 members of the European Parliament subject to a preliminary investigation for allegedly employing party operatives as parliamentary aides.

The affairs are prosaic and complex but starkly echo the presidential campaign, when accusations of enriching family members sank mainstream right candidate, Francois Fillon. Macron has made a law to “moralise politics” his first major legislative test, with surveys constantly showing that honesty is the most sought-after quality in politicians for the French.

The current controversies have put a grain of sand in the REM machine. If this proves to the point of putting a major brake on Macron in the Parliament, his great revolution risks dying in the egg. Again the French glass would look distinctly half-empty.

France is not out of the woods yet, and these parliamentary elections will be a watershed.

Emmanuel Macron’s election will change Europe

Does the French presidential election, after the American one, confirm Friedrich Nietzsche’s assertion that “every profound spirit needs a mask”? The shallow spirit, by contrast, is usually plain to see and can be found on American reality television.

Emmanuel Macron is the moderate revolutionary France needs

The dominant sentiment is one of relief that centrist Emmanuel Macron has won through to the second round of the French presidential election. Barring some sort of political accident, it’s now highly likely he will be the next president of France.

The sorry spectacle of the French presidential election

A far-left candidate’s meteoric rise has given a surrealist hue to the already remarkable French presidential campaign. Heading toward the Sunday election, firebrand radical Jean-Luc Mélenchon is among four top candidates polling within a margin of just 4 percentage points.

The outcome is too close to call. But it’s possible that at least one extremist will reach the May 7 runoff. That both finalists will be populists — one from the radical left and one from the radical right — cannot be ruled out.

Avuncular, loquacious, with a touch of the litterateur about him, Mélenchon, 65, is in fact a soak-the-rich revolutionary who champions Russian President Vladimir Putin and whose political hero is Hugo Chavez, the late Venezuelan leader who ruined his oil-rich South American country — inflation is running at more than 1000% in Venezuela today).

That in a field of 11 candidates, Mélenchon — who wants a top marginal tax rate of 100% — has a following at all, together with far-right National Front candidate Marine Le Pen, shows the farcically low level — the surrealism — of current French political debate.

France’s weak economy, squeezed wages and

high debt and deficits may solidify its voters’

embrace of populists.

This is the first time in half a century that one of the two major French parties is not certain to make the second round of a presidential election. It’s also unprecedented that a first-term president has decided not to run for reelection — a clear admission of failure by President François Hollande.

Of the top four candidates, centrist independent Emmanuel Macron is at 22%, according to an Ipsos poll (down 3 percentage points in the last three weeks); Le Pen is also at 22% (and trending slightly downward), while Mélenchon, barely into double figures a month ago, is now at 20%, having just overtaken the scandal-riven establishment conservative, François Fillon, at 19%.

Another opinion poll, by Elabe, may explain the sorry spectacle. After a television debate, viewers were asked which candidate best reflected their preoccupations: Mélenchon came in at the top, with 26% of the respondents connecting with him; Le Pen, 14%, and Philippe Poutou, a Trotskyist outlier, third at 12%.

That 52% of the French said they felt closest to one or another of these anti-establishment candidates shows the extent of what one analyst called the French electorate’s “monumental anger.”

For more than 30 years neither the French left nor the right has managed to reverse the nation’s economic decline, marked by de-industrialization, a rigid labor market, unemployment stuck at around 10% and exploding public spending. The last time the national budget was balanced it was 1974.

Britain and the U.S., countries with close to full employment, chose Brexit and Donald Trump; highgrowth Netherlands blocked the ambitions of far-right populist Geert Wilders. Now France’s weak economy, squeezed wages and high debt and deficits may solidify its voters’ embrace of populists who variously reject the European Union, banks, big business, the European Central Bank, a market economy, profits, liberalized trade and German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

Further complicating the mix is the possibility that Fillon may yet rise — precisely because he is at least well-placed to block the populists. France has generally been moving to the right and Fillon, a former prime minister, is viewed as strong on law and order, which resonates given that France remains in a Parliament-declared state of emergency, after 230 deaths and more than 800 injured since 2015 in

terrorist attacks.

The big trouble with Fillon, however, is that he presented himself as the presidential-probity candidate and then trashed his own moral example. After media allegations that he paid family members a million euros for work as no-show assistants, he pledged to stand aside if charged over the affair — until he was, in fact, charged over the affair. That his candidacy is at all viable seems incredible, but the threat of the populists is doubtless one reason. Another is probably that, as corruption watchdog Transparency International has pointed out, 1 in 6 French parliamentarians employ family members.

Fillon is another admirer of Putin, so if he rather than Macron should make it to the final vote against one of the populists, one wonders who Putin’s hackers will be looking to help. If two populists win, though, there will be a political earthquake in France, with major ramifications for Europe and beyond.

TRIBUNE : PARIS, UN RÊVE AUSTRALIEN.

Face à l’enjeu électoral français, le journaliste australien, un temps expatrié en France, se souvient du jour de sa première arrivée à Paris qui correspondait à la mort de Miles Davis. Il décrit la capacité qu’a la France de faire rêver un non-Européen.

French election: Fillon & Le Pen — a tale of moral laxity

A Shakespearian twist is required, perhaps, to comprehend the astonishing scenario of moral laxity and personal enrichment, playing out currently in the Old World kingly court of French electoral politics.

Fear and loathing in Europe as leaders grapple with Trump’s ‘war’

Unfazed by the weight of history, Donald Trump says he will save America — from ISIS, drugs, the relentless march of technology and the demon ills of globalisation — without reaching out across the oceans to other Western democracies.

The far right after Trump and Berlin: it’s time to call a spade a spade

Munich: One of the lessons to be drawn from the ugly Berlin truck attack is that if words are to have a sense in the screaming white noise of modern debate – around terrorism, demagoguery and the rise of the populist right – things must be called by their name, even when half-masked and crouching in corners.

Within an hour of the Berlin massacre, in which 12 people died and around 50 were wounded after a terrorist drove a truck into a Christmas market, a tweeting senior representative of the far-right Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) labelled those who died “Merkel’s dead”.

Will France be wooed by right-wing populist Marine Le Pen, like the US and Donald Trump?

After the stupefying Brexit-Trump sequence, and the Italian referendum result, could far-right National Front leader Marine Le Pen win next year’s presidential elections in France?

The good German – Has Merkel given up on her refugee policy?

The naysayers are calling it a climbdown, but is it? German Chancellor Angela Merkel has stepped back abruptly from her open-arms policy on refugees—or has seemed to. The slogan ‘We Can Do It’ (Wir schaffen das) — memorably hailed as heroic by an Auschwitz survivor in the German parliament earlier this year—has become ‘almost an empty formula’ given the daunting challenge of integrating refugees en masse.

‘If I could, I would rewind time by many, many years, to better prepare myself, the whole government and all those in positions of responsibility, for the situation that caught us unprepared in the late summer of 2015’, the Chancellor said.

Made after her Christian Democrats got a shellacking in Berlin regional elections, the comments were widely interpreted as Merkel’s mea culpa. But an intriguing alternative view discerned the expression — the resurgence even—of Merkel’s conciliatory side, amply evident after the Brexit vote but obscured until now in the ‘storm and stress’ of the refugee crisis.

This was the Chancellor reaching out to pacify her ruling conservative Christian Democratic (CDU)/Christian Social (CSU) bloc, which wants a tougher tone on refugees, and voters who have flocked to the far-right Alternative for Deutschland (AfD) in four regional elections since March. Less a climbdown, then, than clearing the way: broadcaster Deutsche Welle said Merkel’s remarks confirmed that she would run for a fourth term in federal elections next September.

Merkel’s re-election prospects have dwindled due to the local election results but are by no means negligible. The CDU has no obvious replacement and her national approval ratings are still in the 40s. (By way of comparison, French President François Hollande is at 15.) The main German opposition Social Democrats (SPD), with no charismatic leader, has also taken a slide, equally losing votes to the AfD.

Yet Merkel’s diminished popularity should be taken in the context of the scale of her decision last northern summer to wave through to Germany tens of thousands of refugees, mostly from Syria and the Middle East, stranded on a railway platform in Budapest and the socalled Balkan route north from Italy and Greece. Since the Syrian civil war erupted like a geopolitical Chernobyl, Germany has taken well over a million refugees — that is, more than Australia has resettled since the end of the Second World War. The implications, enormous for policy and in terms of national and historical identity, have shaken Germany to the core.

Merkel’s decision is frequently denounced in terms of the challenge it poses — the influx of refugees — rather than the primacy of the values it embodies: humanity, tolerance and the power of reconciling, middle-ground compromise: host countries have obligations to refugees and they to their host countries.

At issue is a kind of rendezvous with global justice, a balancing act between the war-wracked developing world (which knows ‘how the other half lives’ via new media) and Europe’s foundation philosophy, at a time when the United States is being tempted by Donald Trump’s racially divisive approach. Not only have wars in the Middle East killed millions of people since the Gulf War in 1990 but also two recent British reports (Chilcot on Iran and a parliamentary group on Libya) have shown that half-cocked Western attempts at nation-building post-intervention have stuffed up monumentally. Surely we in the West have a moral responsibility to take refugees, even if temporarily, fleeing wars we ignited or ignored or for which we have failed to find a diplomatic solution.

Elsewhere in Europe there has been painfully little echo of Merkel’s humanitarian approach, neither on the Left, mired in confusion, nor on the Right, which has hardened its anti-refugee rhetoric since the start of the crisis in France, Britain and Austria. (As for increasingly anti-liberal Eastern Europe, well, someone must have forgotten to tell the political elite what EU membership is supposed to mean.)

But the corollary of Merkel resisting populism’s rise is that, in comparable terms, the German people have, too. Germany has its ugly history, of course, irreparable for some observers, but the country has stepped up to the plate on refugees and this should be plainly acknowledged, as Obama finally did at the United Nations recently, also citing Canada. Put another way, what might be the approval ratings of a British prime minister or a French president — or an Australian prime minister, for that matter — if they had decided to do as Merkel has done?

Perhaps in ten or twenty years the countries that had the courage and commitment to take refugees in substantial numbers in 2015–16 will have redressed their labour-force imbalances, reversed a declining birth rate and paid for their pension systems. Those prepared to hear the cry of the weak in the long night of the Middle East—facing political uncertainty, even humiliation—will have turned things around, be out front and winning.

Angela Merkel is expected to announce whether she will stand for re-election before the CDU party conference in December.

On Zsofia Boros’ CD release, Local Objects

The second album from the Hungarian-born Vienna-based guitarist finds her embracing a broad scope of music, broader even than on her outstanding debut En otra parte.