Where EU leaders have got it wrong is that Brexit is less a crisis for Britain (though it is that), than the latest manifestation of a deep-seated European malady. A sense of the risk of the EU unravelling is alive in the air in Germany and France because the fear is that Brexit has launched a dangerous dynamic of EU disintegration that, if uncontrolled, may, like Brexit itself, prove unstoppable. Perhaps this is something of which David Cameron, but also Boris “Opt-Out” Johnson, are painfully aware.

Summer of fear: Nicolas Sarkozy the cause of France’s woes, not the solution

Debate surrounding terrorist attacks in Europe this northern summer has morphed into rhetorical overkill, as opportunistic politicians in France in particular focus on “situational dissuasion”, which usually just means regulating access to guns and knives.

Munich shooting rattles German calm despite lack of Islamist threat

Munich: Amid a sense of rising panic, events seemed to happen with exceptional speed in Munich on Friday night. Rain in the air, I was returning home from the central city pool with my 7-year-old, when a blaze of police cars mounted tram-lines as we prepared to cross the street. Moments later came the buzz of choppers overhead. Switching on the mobile flashed the horror of multiple killings.

Brexit: Not all of Europe wants Britain to stay in the union

Might Brexit be a good thing for Europe? There’s a comic wrinkle in watching the British Remain campaign translate the argument that Brexit would be devastating for Europe, when Europe itself is not so sure.

French PM comes Down Under

With a federal election in the offing, the visit to Australia by French Prime Minister Manuel Valls to mark the $50 billion submarine contract earlier this month, apparently couldn’t be made to last more than three hours.

Refugee crisis in Europe: civilisational clash or the necessity of reconciliation?

One of the remarkable ironies of the current refugee crisis in Europe is that the One World idealists of yesterday have become the bearers of a certain realpolitik today. As critics of German Chancellor Angela Merkel would have it, ‘those people there’—refugees fleeing Year Zero destruction in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq—are now, well, over here, with us in Europe and the West.

The realpolitik exists in both macro and immediate terms. The crisis has made clear that immigration policy is no longer a matter of whether to accept non-European non-Christians in our midst but is now about how we might adopt and integrate them, and they us, of course — because it must work both ways. A reconciling, mutually engaging relationship is required, because the civilisational ‘clash’ of the major alternatives doesn’t bear thinking about, and for practical reasons of…realpolitik. Whatever happens to the passport-free Schengen zone comprising twenty-six European countries, mass migration from poor Africa and the war-torn Middle East won’t stop when the guns finally

fall silent in Syria. Only a few kilometres of water separates Turkey from Europe’s southern borders, and desperate, shell-shocked people — primed with a detailed awareness of how the ‘other half’ lives due to social media — want a better life for themselves and their families.

And in the macro sense? Islam is now the world’s fastestgrowing religion, with adherents likely to compose 29.7 per cent of the world’s population by 2050 (by comparison, Christians will make up 31.4 per cent). A Pew Research study last year estimated that Christianity would lose about ten million people to atheism and agnosticism in the period to mid-century. Others risk being ‘lost’ to Islam—especially young people, because, as the late British historian Tony Judt observed (in his 2005 Postwar, A History of Europe Since 1945), Christianity is increasingly associated in countries like France and Spain with old age, isolation and the emptying rural backcountry. Whereas Islam is increasingly a source of communal identity and collective pride in the big immigrant suburbs of London and Paris, Christianity is increasingly seen there as a religion for Mum and Dad, who don’t go to church much any more anyway. (In France as a whole, only one adult in seven acknowledges even attending church and then on average just once a month; in Britain and Scandinavia the figures are even lower.)

As European Parliament president Martin Schulz said earlier this year, the EU, with a population of more than 500 million, ought to be able to absorb a million refugees, especially if all member countries play their part. Surely it is unjust that Germany—albeit the richest and largest EU country—is having to bear such a brunt: 1.1 million new arrivals in 2015. By contrast, Britain has pledged to take 20,000 refugees over five years.

Whereas Islam is increasingly a source of communal identity and

collective pride in the big immigrant suburbs of London and

Paris, Christianity is increasingly seen there as a religion for Mum

and Dad, who don’t go to church much any more anyway.

Pan-European concerns about overcrowding and social cohesion are of course understandable but must seem entirely relative seen from, say, Istanbul or Cairo, when Europe is home to just 9 per cent of the world’s population but produces 25 per cent of its GDP and undertakes 50 per cent of its public spending (figures Merkel has used). Creative policy-making is required, and there’s already been some in Germany and Sweden, to streamline processing, spread settlement and get refugees into language training and jobs.

Unlike Australia, Europe has been historically disinclined to use immigration as a policy tool to compensate for flagging birth rates—perhaps mistakenly, given that nineteen of the twenty countries with the lowest birth rates are European (Japan is the exception). It’s amazing for a multicultural Australian to contemplate, but a certain Britain and particularly a certain France still looks back on post-colonial immigration as the period when the break was regrettably, if necessarily, made with a poetically changeless old Europe — that dirty little train steaming out of the station, the battalion band playing for all it was worth, purple afternoons in the hills and all that, to borrow from English playwright John Osborne describing British India.

Immigration from the old colonies was something imperial Europe assumed that it had to accept—not so much as a modernising opportunity necessarily, but as part of the post-imperial burden, for France regarding North Africa and for Britain, the Indian subcontinent.

The events of New Year’s Eve in Cologne, when women were assaulted and immigrant men were the chief culprits, have raised important questions of cultural interface, social cohesion and capacity. Relative to the West, it is probably true that even the most enlightened Muslim societies impose varying degrees of restrictions on women. But one feels uncomfortable, or ought to, bundling the world’s fifty Muslim-majority countries into one basket. As Melbourne University professor Abdullah Saeed has pointed out, there is substantial diversity and difference between the ways men and women interact in different Muslim countries, and frequently these are culturally determined. Often depicted in the West as deeply conservative, Iran, for example, has female professors, parliamentarians and bureaucrats at all levels of society, while in Turkey, Indonesia and Bangladesh, women have held the positions of prime minister and president.

Since the refugee crisis began, the human drama of media interviews with new arrivals in Germany has been eye-opening. The suggestion is often that, because refugees come from countries that don’t respect democratic freedoms, they won’t respect them when they come to a new country, but it is precisely because they are from those countries that they do respect such freedoms. On the BBC an elegant Syrian with excellent English patiently explained her understanding of Western freedoms (of expression, association and the media), before adding that she did not want to have to jettison her religion. Perhaps we’ll know that success on integration is approaching when she no longer feels that we think that she should.

It is often said that the Australian experience of immigration is not applicable to Europe. Girt by sea, we’ve run a managed immigration program for more than fifty years because we can (like Japan or Canada). But we do know from national experience that second- and thirdgeneration migrants, as well as firstgeneration migrants, tend to want to integrate—that is the usual, even natural propensity. If that isn’t the case in parts of Europe, then why not? And the ‘why’ — that why there — lies at the heart of the challenge of large-scale immigration, or at least of dealing with the problem as it actually is. Of the realpolitik, if you will.

On Markus Stockhausen / Florian Weber’s CD release, Alba

Alba is the premiere recording of trumpeter Markus Stockhausen’s duo with pianist Florian Weber, a formation in existence for some six years now.

Refugee crisis: European reaction will add fuel to terrorist fire

Overshadowed by the Brussels terrorist attacks, Europe may decide not to change what isn’t working in its faltering attempt to meet the refugee crisis born of the Syrian civil war. To make operational the recently signed migrant return deal between the European Union and Turkey, European governments will have to relieve the “burden” on Germany and Greece by taking more refugees. It is by no means certain that they will.

On Markus Stockhausen

If a trumpeter’s sound grows pinched in later years (Miles Davis), scribbling (Don Cherry), or it thins (Freddie Hubbard), Stockhausen’s seems to have reached a glorious peak.

In the girl one sees the woman; in the man, the boy? Meeting Markus Stockhausen in the wings after a duo concert in Germany reminds me of his 1980s performance photos: no longer a boy even then, but boyish, wraithlike, something of Peter Pan in the regard. A web check confirms the pictures are of famous papa Karlheinz’s sui generis late creation Donnerstag, that stunned audiences and left one critic remembering the “brilliance” of trumpeter Markus more than 30 years later. On stage earlier, he produced a trumpet sound of such startling bell-like resonance and beauty that one was left floating, adrift suddenly, wondering whether spirits might live in the trumpet of Markus Stockhausen.

I remembered that young Mozart reportedly passed out when he heard a trumpet played in the open air for the first time. On his new CD Alba with recent Lee Konitz pianist Florian Weber (Stockhausen’s first for Manfred Eicher’s ECM in 15 years) there’s a track – just a fragment really – where he blasts impromptu trumpet notes into the body of Weber’s piano. The effect is mesmerising, transporting, as of a glorious colour field slowly rising.

For a telephone interview three months later, he comes on the line saying he doesn’t want to talk about music in “conventional terms”. The facts-based approach I presume, of influences, discographies, practice routines. But I would like to ask about one of the most significant father-son relationships in modern music. He recalls rocky moments in the 90s, Markus making his way now as a polygenre trumpet-player, neither jazz nor classical but clearly sourcing both – until the break. “In a way our final farewell started in 2001 when I decided not to play his music anymore, and I went through all kinds of feelings – of guilt; of missing him. It was like this long fade, so when he died (in December 2007), it was another step in that feeling of farewell.”

Stockhausen’s improvising ability was plainly evident early – hear his bright-toned Strahlenspur solo on Rainer Brüninghaus’s Continuum (1984) – but it was perhaps only after his father’s passing that true colours really started to come. Out from under, the technique that made jaws drop began to be channelled more effectively. The sound certainly changed, growing fuller, rounder, developing this magnificent, steely resonance.

Prompted, he talks about Freddie Hubbard’s First Light as a major early influence, the visionary Miles of In A Silent Way and Bitches Brew, and Kenny Wheeler for his sheer musicality. Yet at a rigorously cleanliving58, Stockhausen’s tone is probably fuller than Freddie’s ever was and certainly than it became. If a trumpeter’s sound grows pinched in later years (Miles), scribbling (Don Cherry), or it thins (Freddie), Stockhausen’s seems to have reached a glorious peak.

In the decade to 2012, he tells me, he put out 12 CDs of his own music on his Cologne-based Aktivraum label. But there was plenty of other music on other little labels. Taken together, this may be why the recordings are not better known. Still, there’s some very fine improvisation on Joyosa (2004) – his solo on Mona a melodious gem – the exquisite Streams with guitarist Ferenc Snétberger (2007), or Electric Treasures (2008), a live small group recording with pianist Vladyslav Sendecki that is a veritable cracker.

Partly for having lived through the demanding rigours of father Stockhausen Inc. – musicians starving themselves for days before performance and so on – his capacity to blend into musical contexts set by others is remarkable, and rare for a trumpet player (not generally retiring types). Room-transfiguring moments open pianist Antoine Hervé’s Invention Is You (2001), while on Michel Portal’s excellent Dockings (1998), Markus very nearly takes the honours.

Twenty-five years of intense closeness with the dominant post-war composer however, inevitably left their mark, not least by imprinting the primacy of music’s spiritual dimension. “Improvising is one of the most intimate things you can do with another person. It comes very near to love-making,” he says.

Today, about half Stockhausen’s time goes on the duo with Weber, another with clarinettist Tara Bouman, and his highly original Quadrivium quartet. Much of the rest is dedicated to seminars and conferences called “Singing and Silence”, “Healing Sound” and “Intuitive Music” (a term conceived by Stockhausen Snr). Why so? “First because of my own personal quest and this inner need to be in that spiritual sphere. Sometimes it’s even more intense and nearer to me than in certain concerts, which have more of a virtuoso or entertainment aspect.” That intensity can be tested on Alba (released this month) and when Stockhausen and Florian Weber appear at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester on Tuesday 31 May.

Picture: Gerhard Richter, www.richterkoeln.de

On Ferenc Snetberger’s CD release, In Concert

The ECM debut of Ferenc Snétberger features the widely-acclaimed Hungarian guitarist in solo performance before a rapt audience at the Liszt Academy in Budapest.

Angela Merkel: principled, pragmatic and now at risk

Angela Merkel is on the political rack, blamed from all sides for exacerbating the refugee crisis that she alone among Europe’s senior political leaders was prepared to meet. As if the world’s war-ravaged and desperate arrived on Europe’s southern beaches because the German Chancellor appeared in a selfie at a refugee shelter in Berlin.

Shame of Cologne should not obscure the horrors of Syria

In the febrile arena of current German public debate, prudence should be the byword. But it isn’t. No one would want to appear an apologist for the molestation de masse in Cologne on New Year’s Eve – when a group of men descended on unsuspecting women in the half-light of the city’s central square. But some of those condemning it are also seeking to profit from it.

Marine Le Pen is far from finished

The French hair-trigger? Just another lurching crisis from the nation that gave us the modern revolution? The media frenzy that greeted the far-right National Front (NF) winning the first round of French regional elections on 6 December, will now as with previous surges, more-or-less quickly subside.

Marine Le Pen’s National Front blunts chance for reform in France

Can the French National Front’s Marine Le Pen win the next French presidential elections in 18 months? Can the leader of an anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim political party — not merely anti-radical-Islamic — take the reigns of one of the world’s great democracies?

The question beckons after historical gains for the far-right National Front in the first round of French regional elections at the weekend. Final results won’t be known until after second-round voting next Sunday, but Ms Le Pen, 47, may be unassailable in the Picardy Nord-Pas-de-Calais region of six million people in the nation’s north. Her niece Marion Marechal Le Pen, 25 — who last month said Muslims could “not truly be French” — was a clear leader, also with 40 per cent of the vote, in the southern region of Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur.

According to the French Interior Ministry, the NF was leading after first-round voting in six of 12 newly established mainland administrations with 28 per cent of the vote nationally. Created in 1972, the Front has never governed a French region.

Nord-Picardy is the place of immediate implications for Australia. Under a territorial reform passed by the national parliament last year, the enlarged Nord-Picardy encompasses the French Western Front that includes such historically and spiritually important places for Australians as Villers-Bretonneux, Fromelles, Pozieres and Bullecourt, the sites of key World War I battles.

A victorious Madame Le Pen would be Picardy Nord-Pas-de-Calais Regional Council president, so a requisite invitee to Anzac Day commemorations in the Somme and northern France. French Regional Councils are elected for six years.

The NF’s weekend electoral success completes an impressive triumvirate that began with local council elections last year. The Front won 11 municipalities — trebling its 1995 score — secured a district of Marseilles, the big immigrant city of the south, and two French towns with a population of 50,000 or more (Beziers and Frejus). Two months later, it topped European elections in France, winning 25 per cent of the vote.

Yet the Front’s most high-profile result was in 2002 when founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, a former paratrooper, defeated Socialist candidate Lionel Jospin at the first round of presidential elections. Both sides of politics joined forces, an emboldened electorate rallying in the streets, to carry Jacques Chirac over the line with a Soviet-type score in the second-round run-off.

The cry was jamais encore (never again) but in fact things were better economically in France then than now. In the dozen years since the social problems undoing France have shown no sign of significant improvement. On the contrary. Unemployment has just risen to almost 11 per cent and in the housing-estate suburbs that border most big French cities it is much higher than that. The jihadi attacks in Paris added a new level of anxiety. According to French political scientist Gerard Grunberg, for many voters “there is an Islamic peril in France and we have been too tolerant towards it”.

Meantime, Le Pen, Jean-Marie’s youngest daughter, has had a degree of success in laundering the party’s image. Since taking the leadership four years ago from her father — who referred to the Nazi gas chambers as “a detail” of history — she has shrewdly combined old Left protectionist economic policies with a tough line on immigration. A handful of high-profile defections by newer party officials (frequently of non-French origin) dinted her popularity, claiming that only party window-dressing had changed — at the back of the shop, the Front was still xenophobic and sexist.

But a dent is all that it proved to be. Le Pen fille and the NF were expected to surge in the first electoral test for the French political class since the November 13 terrorist attacks. However, opinion polling has also shown a double-digit jump in approval for Socialist President Francois Hollande.

Security crises usually mean a boost for political incumbents yet the irony of the fillip for Hollande may ultimately help Le Pen. If she can defeat Hollande at the first round of the elections in 2017, she is unlikely to win against a candidate of the mainstream Right in the run-off, be it former president Nicolas Sarkozy or former prime ministers Alain Juppe and Francois Fillon.

However, if Hollande is her opponent and France’s economic fortunes don’t improve, which is likely, it is by no means certain that la France profonde (deep France) would vote to return a centre-left president. This would make Le Pen president of France.

For Australia? How far Le Pen goes is in a sense a secondary consideration. The fact of her rise and rise, and the consequent loss of authority across the centre of French politics, has further blunted the prospects of serious economic reform in France. Sustained incapacity to fix the supply side of the economy, with its overly regulated product and labour markets, risks reducing the appetite of international business for trade liberalisation and investment in Europe’s second-largest economy.

Ms Le Pen is doing damage. The uncomfortable truth is that worse may still be to come.

Comeback trail: Déja Vu Sarkozy Part Deux

Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy is poised to begin another comeback this weekend in a conservative party leadership election. But as a journalist who worked for the Australian foreign service in Paris argues, he must first woo France’s political center.

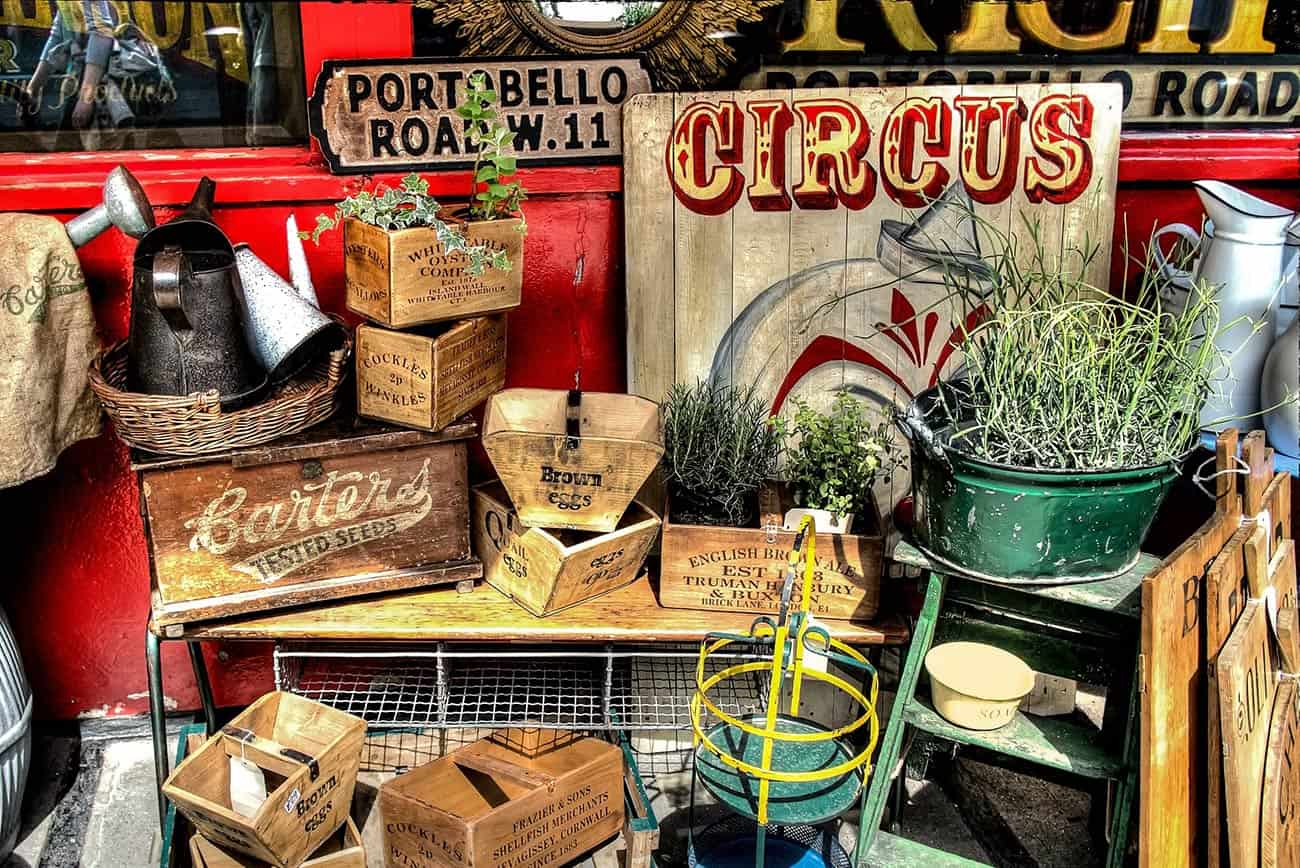

Paris, and all that jazz

The romance of jazz in Paris still resonates. Take a walk up rue Mouffetard or the little knot of streets around St Germain and you keep bumping into tiny fragments of it. The postcard photos of Miles and Charlie Parker evoke that postwar period where the Left Bank Paris of Sartre, cafés and long cigarettes jumped off from reality into myth.

Fifty years on, if more by chance than design, the focus of jazz in Paris has moved from the Left Bank to the Right and especially a handful of clubs on a street near central Châtelet: the Sunset-Sunside, the Baiser Salé, and the Duc des Lombards, which reopened in February after seven months of renovation.

Comparing rue des Lombards with New York’s 52nd Street in the 1940s would be an overstatement (though a French newspaper couldn’t resist recently), but its vibrancy is testament to the elevated position that jazz still holds in the cultural reckoning here. Jazz provided the soundtrack to the “literary genius” and archly leftwing politics of existentialism, and later, French cinema’s nouvelle vague. Today, like France itself, jazz has moved to the right – outwardly at least. The revamped Duc des Lombards, with its muted interiors and designer chic, looks like the kind of club that President Sarkozy and his wife Carla would visit.

For years, patrons of “Le Duc” were greeted by a giant exterior mural of saxophonist John Coltrane. With investment from new owner Pierre Vacances and chief executive Gérard Brémont, the club has been refurbished using the music of “The Duke” (Ellington) as the leitmotif. “Black, Brown and Beige”, the title of the master’s extraordinary suite, are the colours of the main ground floor room, while an electronic curtain behind the bandstand reproduces images inspired by Ellington songs.

The Duc has overturned the old jazz club practice of three separate “sets” until the wee hours, with two concert performances of 90 minutes at 8pm and 10pm. In a stroke, artistic director Jean-Michel Proust has made a weeknight outing to a jazz club something conceivable for locals and visitors.

In an ambiance that a local critic called “San Francisco beatnik”, an outsized pole used to obstruct views of the stage but now vision is good, including from upstairs. And with food on offer by Alain Alexanian, Michelin-starred for a restaurant in Lyon – reckon on spending about €35 for a meal – “Le Duc” feels like a very classy act.

A stone’s throw away, Le Sunset-Sunside is in fact two clubs – two bandstands, bars and two club rooms – accessible via the one entrance. The Sunset was the first club on the street, established in 1982, and began life with a jazz-rock bent (interestingly, that stream of jazz came to Paris later than London or New York).

But programming became eclectic long ago. Joined by the Sunside in 2000, the Sunset has always sought to highlight the best French players – early in the week, when it’s hard even in Paris to fill a jazz club, Monday nights are a jam session and Tuesdays are given over to the “New Generation”.

Yet top-flight Americans also feature: Brad Mehldau, Steve Grossman and Wallace Roney, in the last year or so. “I don’t like jazz in compartments,” says owner-programmer, Stéphane Portet. But it’s fair to say, as at Le Duc, a modernist brand of hard-bop dominates. Sit up front and the closeness of the musicians – of the sound of wind on brass – makes both clubs excellent places to hear modern music.

Just next door, Le Baiser Salé is home to African jazz in Paris – but by no means exclusively so. Last weekend, one of the most exciting of the current French players, Pierre de Bethmann, performed a tribute to Herbie Hancock’s post-Miles Davis electric music. Jazz or jazz-related singers are also a regular fixture.

If nostalgia for Left Bank Paris takes hold, Le Caveau de la Huchette is a venue where time seems to have stood still. Swing and boogie-woogie are the main events, in a setting to soften the heart of even the most avant garde tastes.

By all accounts, “Le Caveau” hasn’t changed much since the Left Bank New Orleans revival – which happened about 40 years ago. The Doriz family have been its proprietors since 1969 and have hardly ever missed a night.

Where to hear it

Le Duc des Lombards, 42 rue des Lombards, tel: +33 (0)142332288

Le SunsetSunside, 60 rue des Lombards, tel: +33 (0)140264660

Le Baiser Salé, 58 rue des Lombards, tel: +33 (0)142333771

Le Caveau de la Huchette, 5 rue de la Huchette, tel: +33 (0)143266505